Forecasting Feed Needs

An abundance of first cut and a cautionary tale

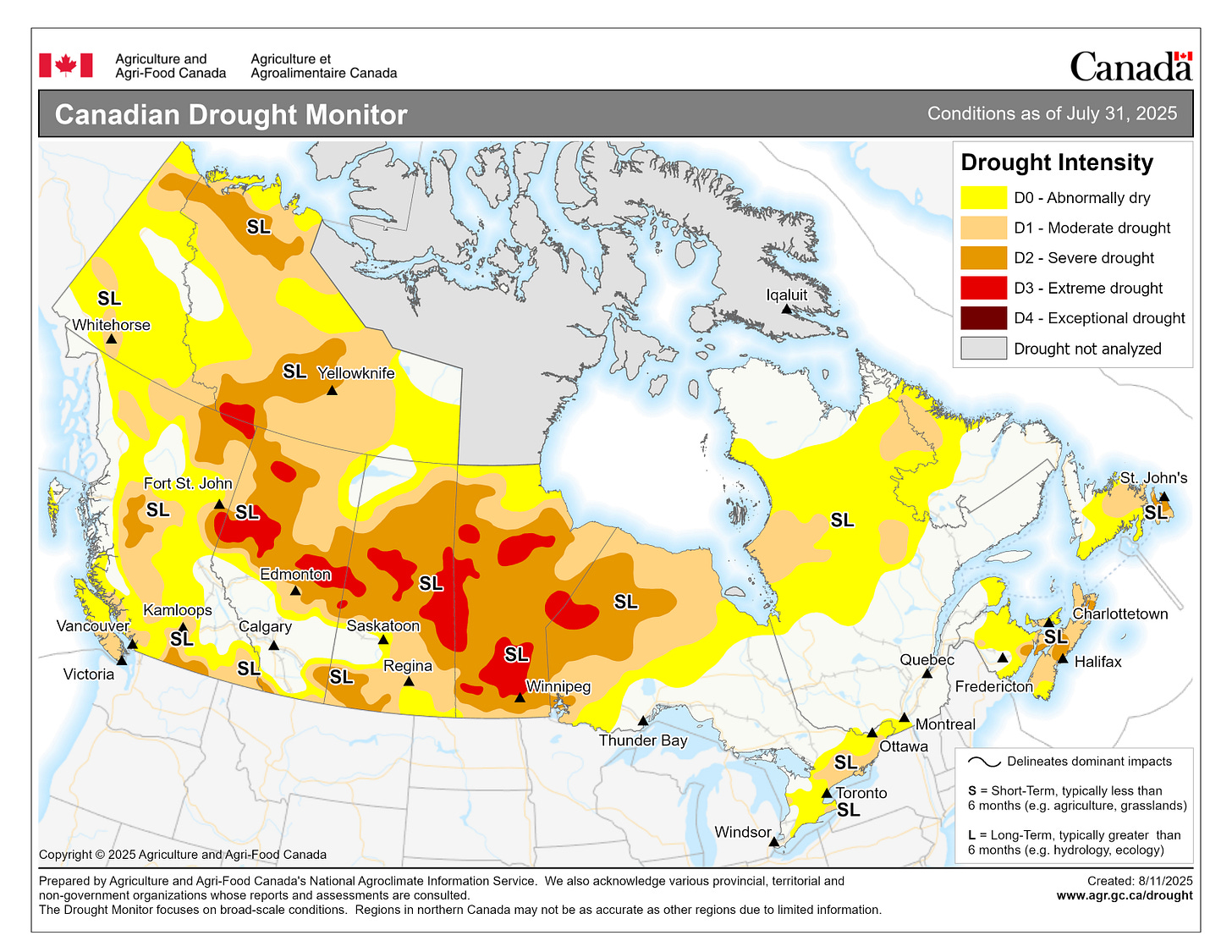

First cut this year was late in many regions or plagued with rain. It was also bountiful judging by the quantities for sale. Second cut should be well underway, but I still see a fair number of fields with first cut standing in my part of Quebec and my travels through eastern Ontario. I ventured into central Ontario in late July, and it was shockingly dry. The Drought Monitor shows about 71% of agricultural lands in Canada are abnormally dry, extending all the way into an extreme drought in some regions.

At this stage, I’ve been farming long enough to know the next drought could just be one season away. The state of our stockpile of hay is checked frequently. Forecasting your farm’s feed needs is a vital part of operations. It’s necessary to calculate a feed forecast so you can also plan out any cash outflows associated with feed purchases. This applies to all farms with livestock, not just sheep operations.

Unfortunately, there is a whole country that has droughts so frequently, they have very detailed calculators on how to figure out feed requirements. Numerous Australian resources exist for meeting forage needs in a drought situation if you’re looking for more information that put I’ve put together here. I’ll focus a lot here on forages, but the same factors will apply to other feeds needed.

Components of the Calculations

Forage is the foundation of feeding ruminants. There are other approaches; however, they are beyond the scope of this article and should be done while working with a qualified nutritionist. Everything in these calculations is done on a dry matter (DM) basis because hay will vary from field to field. A hay analysis is key information to have on-hand so that you can optimize your feed rations and have values to track. You can use benchmark values to make an estimate, but without an analysis, you are guessing at best.

For the purposes of all the calculations used in this post, we are going to assume you are buying dry hay with a dry matter (DM) value of 85%. Most of the dry hay I’ve seen has DM values ranging from 88% to 78%. Knowing the DM value and using that for your calculations matters because silage bales (also called haylage, baleage) weight more while having a quantity of feed due to the water content.

Next, you need the dry matter intake requirement for your livestock. This is where a ration program is helpful, as you can figure out the exact needs per stage of production of your animals. There are several free or paid options out there for ration programs (Montana State has one for sheep). I’ve put together a shortlist of the daily dry matter intake for various livestock for you to use if you don’t have a ration yet.

Sheep: 2-4% of body weight

Beef cattle: 1-3% of body weight

Goats: 3-5% of body weight

Horses: 1.5-2% of body weight

All the calculations will be in imperial pounds because hay typically sells by the pound. At the time of writing, hay varied from 7 cents to 18 cents per pound. If you need to convert kilograms to pounds, multiply the kilograms by 2.205 (welcome to Canada where we use imperial and metric and remember a ton and a tonne are not the same!).

Wasted feed

It’s worth taking the time to monitor how many bales you use in a year. We have a notebook on the kitchen table to track hay, straw and other bulk purchases. This is valuable information as you can then determine if your required hay calculation makes sense. It also helps to determine how much waste you have. Your calculations are going to need to include a percentage wasted, whether this is hay that as gone bad from insufficient storage or the animals trampled it.

Silage bales will traditionally have more waste, as the smallest tears can cause significant spoilage. Different storage techniques will have different spoilage risks. Individually wrapped bales have the lowest risk factor, but are also the most expensive. Bunk silos and ag bags typically work best for larger operations, as you need to be able to feed at least a foot per day to keep the bag or bunk face fresh. Tube-wrapped bales work well and are cost-effective, but when there is a hole, odds are more than one bale will be impacted by spoilage.

Different feeding systems will also have waste factors. If you will be short on hay, limit feed the hay and do not just throw an entire round bale at the animals. All feed systems have some waste but some more than others. If the animals can pull feed back from the feeders, you can easily be looking at a 30% waste of hay. Fenceline feeders that limit the ability for the animals to pull in feed and control how much they have access to will have much lower waste, around 3-10%. Most well-designed bale feeders have around 10-15% of waste. Some methods, like bale grazing, have calculated the return on the wasted feed for later nutrients in the soil, but regardless, your hay needs calculation should include a waste and spoilage factor.

Timeline

You also want to monitor how many days you need to feed hay. If you are grazing, this can vary year to year so you should aim to maintain a buffer for the days calculated. In the example, we are going to do a calculation to feed sheep from June 30th of one year to June 30th of the next year (365 days). If you are feeding silage, keep in mind that those bales need to stay wrapped for 3–5 weeks minimum before you can open them. So even if you are cutting hay the first week of June, your feed stockpile has to last into July. Having to look for hay in late May is not fun at all (been there, done that).

Following hay prices will also help you determine how much you should have on hand. Whenever possible, having extra hay on hand is never a bad thing, as droughts are being more likely each decade. Normally, you should aim to have all of your hay purchased before the end of September (depending on where you live, the end of the last cut). You want to avoid having to buy have between January and June, as prices during those times rely a lot on the prior year’s supply. In short, buy, and produce as much as you can during hay-making season.

Final Calculation

To make the final calculation, you need:

Daily dry matter intake requirement of your livestock (sheep, 3%)

Average weight of your animal (sheep, 135lbs)

Number of days you need hay for (365 days)

Number of animals you intend to feed (100 sheep)

Dry matter value of the hay you plan to use (85%)

Waste and spoilage factor for your system (15%)

Once you have this information together, follow these steps:

Daily DM intake x average weight x days on hay = DM hay needed per animal (in pounds or kilograms)

DM hay requirement x number of animals = total hay needs on a dry matter basis

Convert to the actual amount by taking total hay divided by DM value of hay

Increase the amount by multiplying the actual amount by 1 plus the waste factor

Example using values listed above:

DM hay requirement 3% x 135lbs x 365 days = 1,478lbs

DM total hay requirement 1,478lbs x 100 sheep = 147,800lbs

Actual hay needed 147,800lbs divided by 85% = 173,882lbs

Total hay needed including potential waste = 173,882lbs x 1.15 = 199,965lbs

You can also break down your need by production stage for each animal based on your feed ration. This will give you a more precise number. Not all hay is equal, so the more detailed you can get, the easier it is to control your purchasing decisions. If a seller of hay cannot provide the weight of the bales or a hay analysis, proceed with caution.

Once you have the number of pounds of hay you require, you can convert that to a per bale number. Using the above example requirement, here is what that might look like:

4×5 large round bales, estimated to be 850lbs each, you would need 235 bales

large square bales, estimated to be 1200lbs, you would need 166 bales

4×4 smaller round bales, estimated to be 500lbs, you would need 399 bales

Other Considerations

The more detailed your calculation can be, the better. As demonstrated by the above example, the main factors impacting your buying decisions are the daily DM requirement per animal and the waste. Using rations and improving your feeding system to reduce waste will help you control how much hay you require.

When looking at hay to buy, a hay analysis and a weight per bale or simply buying by the pound will help reduce the guesswork. The hay analysis will have several values on it. Some key ones to consider:

Total digestible nutrients (TDN) – higher is better, straw is around 39%, look for hay over 50%

Crude Protein (CP) – higher is better, for comparison, straw is around 5%, look for hay over 10% unless the price reflects the lower quality. Dairy quality usually means a CP over 18%. Check the nutritional needs of your livestock to know what you need in terms of protein, as it is the most expensive ingredient to replace.

Relative feed value (RFV) – higher is better, look for hay with a value over 90, alfalfa can easily get 130 or more while late cut grass poor quality hay will be around 60.

Relative forage quality (RFQ) – higher is better, straw is around 45, minimum for decent hay should be 100, lactating animals should have around 140-160.

Different stages of production have different needs, which means you can try to source hay at different levels using hay analysis and rations to optimize your spending. This paper from South Dakota State University has a decent explanation of looking at hay using RFV and RFQ when making purchasing decisions.

I hope this helps you determine how much hay you will need going into winter. Being able to plan ahead is critical to the survival of your operation in adverse times like a drought. If you know how much feed you require until the next growing season, you can plan out your purchases in line with your cashflow. You can hopefully make purchases during the hay season, not in the winter at peak prices.

Thanks for reading! I hope you’ve had a good summer and that you are getting rain. We’ve gotten two cuts, but the third is looking rough. We should have enough feed thanks to our ongoing forecasting models and hay hoarding tendencies.

I would say one of the most important things is to check you bales for weight. Most "4x5" bales ive seen are more like 4x4.5 and bale densities are all over. You may think you have 100 000 lbs of hay when you actually could have considerably less.